Kate Mukungu writes about the recent workshop on Gender-Based Violence held at Northumbria University

Three weeks to the day after being part of Transforming Cultures: A Trans-Atlantic Conversation about Gender-Based Violence, I have given myself a maximum of 30 minutes to write down the impressions that have stayed with me from the session (I am a super slow writer so this is somewhat of an experiment!). If you are anything like me, you will see and hear about way more interesting events than time permits you to attend. These days I barely get along to any and I was inches away from giving this a miss. I’m so glad I didn’t.

Cullagh Warnock, an absolute mine of knowledge about activism, policy development and research on gender-based violence (GBV) in the North East of England and beyond, opened her talk with one of my favourite ever academic statements (from Htun and Weldon, 2013). Being reminded that feminist activism, above all else, drives progressive policy and practice on violence against women, made me smile – it was like an affirmation.

We were reminded by Cullagh about a whole host of challenges, many, but not all, caused by austerity. The difficulties of accessing justice following rape & other violence, and the postcode lottery of whether women have access to Rape Crisis support, were presented to us as appropriately troubling. The push back by groups such as the Centre for Women’s Justice, using strategic litigation as a tool to demand change, made me grateful for the energy and skill of others, to keep pushing on in this relentless relay.

The difficulties of accessing justice following rape & other violence, and the postcode lottery of whether women have access to Rape Crisis support, were presented to us as appropriately troubling.

I wasn’t familiar with Susan Maine’s work prior to the session, but my friend Sue, correctly, assured me that I would find her talk rewarding. I was felt sure that Susan had a depth and breadth of knowing of violence against women issues, which confirmed when I heard her responses to the questions from the floor. However, I appreciated her zooming in on a specific issue from her part of the world, so that those of us on this side of the water could better understand. If any of us were unsure about the significance of the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, we were soon relieved of that doubt. With the balance of votes tipped to the right, hard fought gains for women’s reproductive rights, workers’ safety rights and progressive legislation in general, now seem in grave risk.

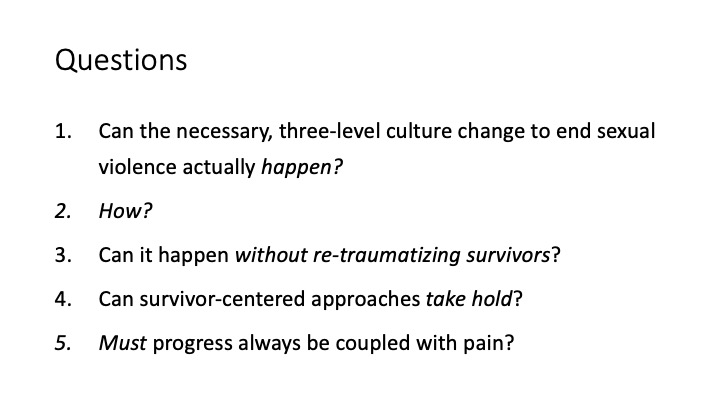

In addition to naming the problem of ‘bro-culture’ and its acceptance through society (we might call it toxic masculinity), Susan posed some poignant questions for the group. In doing so she reflected an uncomfortable truth about the price paid by women survivors who step forward to share their experience, out of a sense of duty. That taking a stand about abuse, seems to invariably result in further abuse, was not lost on us. However, given the current President of the USA’s willingness to mock and deride Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, standards of decorum from the highest public official seems to be one area where regression is evident, since the testimony of Anita Hill in 1991.

The questions and comments from the floor showed how much people in the North East are thinking about gender justice, globally, as well as locally. Whether we were talking about patriarchy globally or right where we were, on campus, we seemed to keep coming back to one particular theme; for all the regressive and scary (oh so scary) developments happening, there are also grounds for hope. Such glimmers come in the activism of younger women and the willingness of people to engage, where previously they may have felt too removed. It felt quite Dickensian by the end of the conversation; that we are in the worst of times and indeed, the best of times.

Kate Mukungu is a PhD student at Northumbria University and Lecturer in Social Sciences at the University of Cumbria

Harvey Weisntein. #Times Up. #MeToo. Abuse by clergy, sports coaches and politicians. We’re in the midst of a newly-energised conversation about abuse, harassment, sexual violence, and conduct between women and men. For those of us who’ve worked in this field for decades, the new attention to this issue is astonishing. The revelations that men’s abuse of women is widespread and frequent are not.

Harvey Weisntein. #Times Up. #MeToo. Abuse by clergy, sports coaches and politicians. We’re in the midst of a newly-energised conversation about abuse, harassment, sexual violence, and conduct between women and men. For those of us who’ve worked in this field for decades, the new attention to this issue is astonishing. The revelations that men’s abuse of women is widespread and frequent are not.