Associate Professor Katy Jenkins reflects on waiting during fieldwork

Trámites, only now do I fully understand the meaning of this quintessentially Peruvian activity. Having yesterday spent five hours traipsing between different local government and council offices, only now do I understand why trámites are approached with such trepidation and given such weight in the Peruvian imagination. The verb ‘tramitar’ is best translated as ‘to process’, so haciendo trámites is essentially submitting oneself to the bureaucratic process. In our case, this was the final stage of trámites that had been ongoing for several weeks, aimed at securing permission to hold a photography exhibition in one of the main streets in Cajamarca city, Peru, on International Women’s Day. So, having submitted various requests in duplicate to various different offices (should it be the mayor; the municipality; the local government, all of these or somewhere else entirely?), I spent yesterday, accompanied by my Peruvian research assistant, going between various offices searching for the elusive permiso – would anyone actually take responsibility for granting it or would it be a request for another document, another thus far unmentioned permission to apply for, another stamp or signature to obtain? We were frequently told that the person we needed to speak to (usually ‘el jefe’) wasn’t there, that we should leave our documents and come back tomorrow, and our requests and documentation were viewed with deep suspicion. Folders were leafed through, computers consulted, colleagues summoned, brows furrowed and heads shaken. Unfailing patience and ingratiating politeness were required throughout, as any one of these officials could decide to reject our request with no reason at all. To an outsider at least, the lack of a clear logic or transparency structuring this process makes it baffling and frustrating in equal measure. Even with the benefit of my research assistant’s ‘insider’ knowledge, this process seems to me arbitrary and at times impenetrable – cultural conventions, tacit assumptions and unspoken hierarchies abound.

These trámites have given me new insight into the, at times Kafka-esque, bureaucratic hurdles of everyday life faced by (especially poor, rural and not always fully literate) Peruvians.

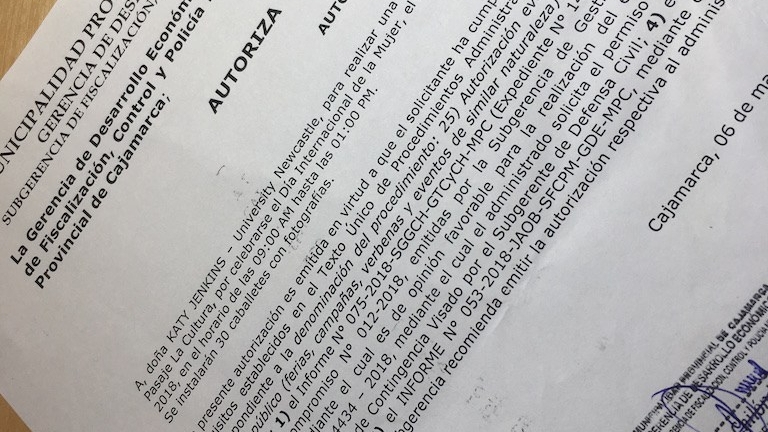

We visited one office of the municipality four times, the offices of the Civil Defence Authorities twice, and municipality offices in a different part of town, twice, each of these visits requiring a 15-minute taxi ride. We have stood in line to pay our fee (when we find out this is required), we have submitted proof of payment, and now today, fingers crossed, we are told the permiso will be authorised. Our one-page letter requesting permission, itself couched in a language of extreme deference to authority and office, has become a seven-page document in duplicate, stamped and signed by, seemingly, half of Cajamarca’s state apparatus. It quickly becomes clear that although we first submitted the documentation several weeks’ previously, it is only by being physically present and endlessly chasing a resolution, that the trámite progresses through the bureaucratic system.

I was always slightly sceptical when people told me they had put aside whole days for trámites, but now I understand a little of the waiting, the frustration, the powerlessness, and the process of deferential ingratiation that is required in order to (perhaps) eventually reach a favourable result

It’s times like this when I wish I did research with a large NGO or organisation that would take care of these sorts of tasks. Working directly with grassroots women’s organisations, themselves often marginalised from, alienated by, or simply unfamiliar with the bureaucracy of local government, makes it difficult to effectively navigate such structures as a foreign researcher. These trámites have given me new insight into the, at times Kafka-esque, bureaucratic hurdles of everyday life faced by (especially poor, rural and not always fully literate) Peruvians. I was always slightly sceptical when people told me they had put aside whole days for trámites, but now I understand a little of the waiting, the frustration, the powerlessness, and the process of deferential ingratiation that is required in order to (perhaps) eventually reach a favourable result, to be given the appropriate paperwork, duly stamped and authorised.

And so we wait, for lunchtime today, to see if our permission is granted, or if another stage of trámites is deemed necessary….

…Two further trips to the municipality and later the same day, just two days before the exhibition, we finally have our authorised, signed and stamped permission document in our hands!

Reflecting on this experience, there must certainly be a case study in here on Weber and bureaucracy for our Sociology students! How is bureaucracy maintained and reproduced? How might bureaucracy produce particular subjectivities? How is bureaucracy experienced, navigated (and sometimes subverted) by different types of people? But for now, at least, I leave these debates to one side, the relief is immense and the exhibition can go ahead!

Dr Katy Jenkins is an Associate Professor in International Development at Northumbria University.

Twitter: @drkatyjenkins