Adele Irving and Oliver Moss introduce their research into homelessness in NewcastleImaging Homelessness in a City of Care was an ESRC-funded participatory mapping initiative, undertaken in the summer of 2014. It was led by Northumbria University and supported by Newcastle City Council, five homelessness charities and 30 members of the Newcastle’s homeless community. The aims of the initiative were as follows:

- to challenge essentialist readings of the “universal homeless subject” (DeVerteuil, 2009, p. 650)

- to improve understanding of the homeless experience, through a focus on the spaces and places of homelessness and the mobilities that co-produce them (Cresswell and Merriman, 2010); and

- to afford a wide range of homeless people greater input into local decision-making about homelessness provision.

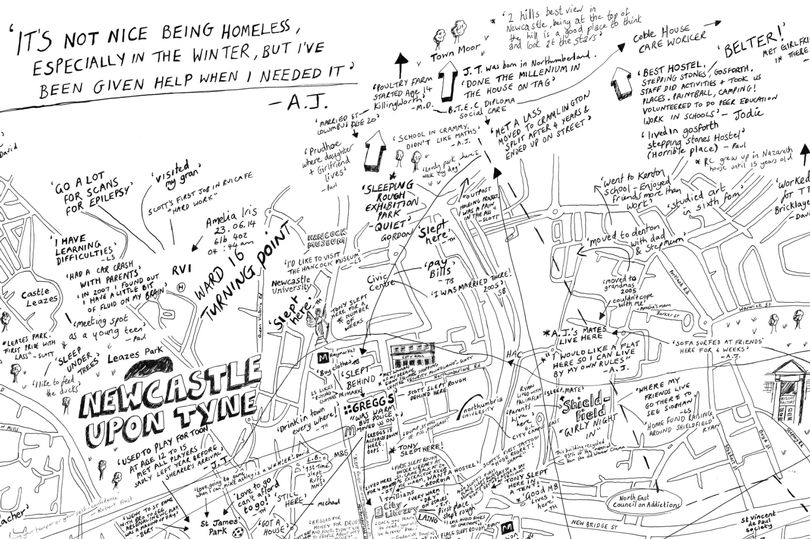

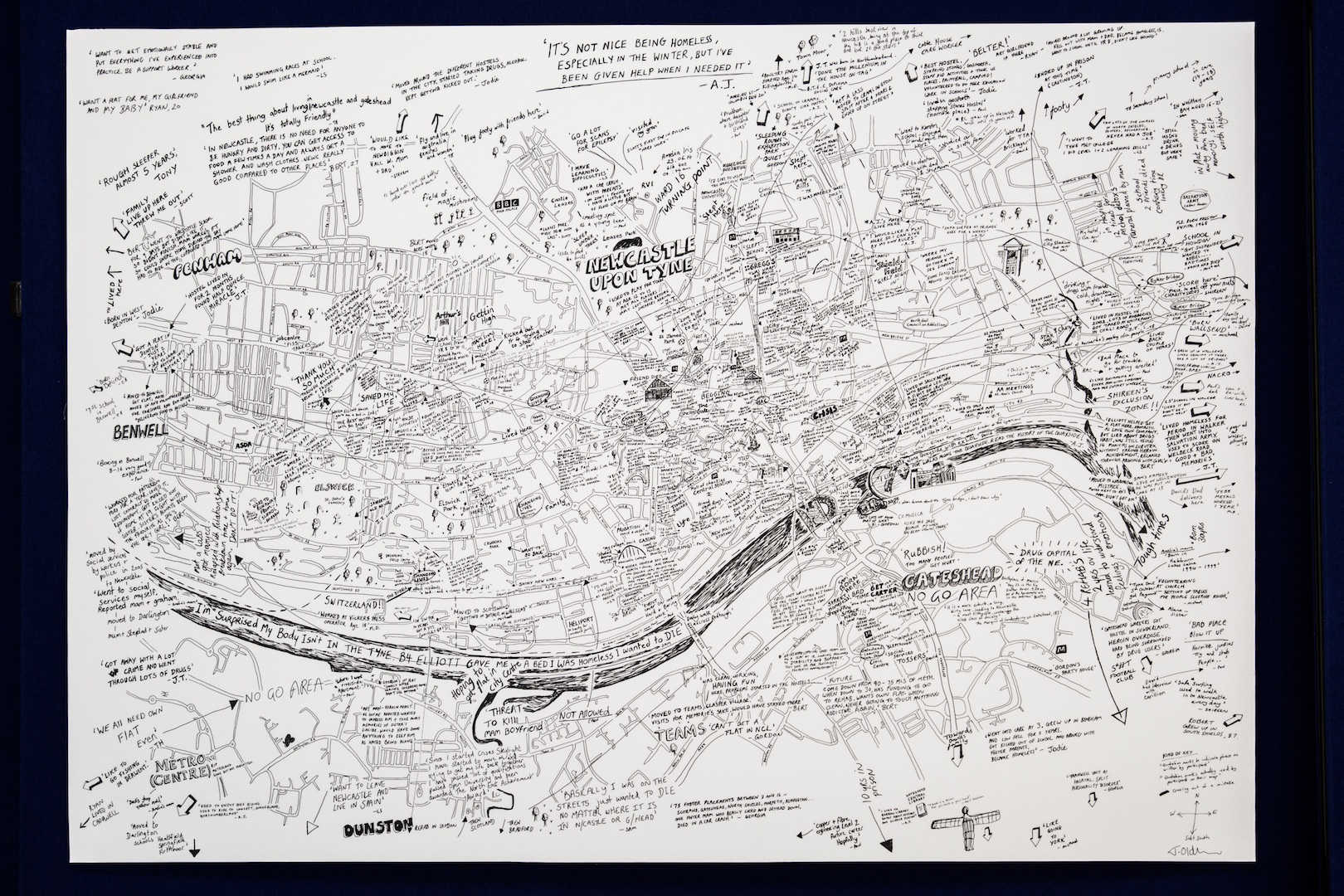

Six workshops were held; each structured around a simple lo-fi – map-making exercise, whereby participants were asked to identify spaces and places within the city of particular material or symbolic importance. These mappings were later shared with the artist Lovely JoJo, who in turn produced a composite map. This, together with the participant maps and selected images from a related auto-photography exercise, were unveiled at an opening event held at Newcastle Central Library in November 2014, as part of the ESRC’s Festival of Social Science. The event was attended by over 60 local policymakers, practitioners and academics. The exhibition then toured around hostels and day centres, public spaces and homelessness conferences. To date, the project blog (www.esrcimaginghomelessness.wordpress.com) has received more than 4,000 hits from 40 different countries, and prompted enquiries from government departments and homelessness charities from within the UK and overseas. The project also secured first prize in the ‘Most Engaging Presentation of Research Data’ category at the 2015 Local Area Research + Intelligence Association (LARIA) awards (www.laria.org.uk/2015/03/laria-research-impact-awards-2015/).

The maps revealed five key insights of relevance to those engaged in the management of homelessness.

Firstly, they demonstrated the diversity of participants’ life experiences and pathways into homelessness. While some participants had experienced a lifetime of exclusion such that their pathway into homelessness was almost inevitable, others appeared to have led relatively normal lives until adulthood, when a significant life event triggered a sudden pathway into homelessness (Harding et al, 2012).

For us, the maps confirmed that the ‘emotional’ matters (Davidson and Milligan, 2004). Emotions, such as “pain, bereavement, elation, anger [and] love” (p. 7) are filters through which we come to know and experience the world, shaping both what we know and how we know it.

Secondly, the maps documented everyday activities such as eating, sleeping and socialising. Participants thus sought to emphasise that they were in many ways no different to the housed public. They did not typically conform to widespread stereotypes that the homeless population is primarily comprised of anti-social vagrants. In highlighting their personal experiences – of joy, hope, sadness and pain, for example – they presented themselves not only as ‘thinking, acting’ others, but fully emotional subjects with needs, desires and a sense of themselves which extended beyond a homeless subjectivity (May and Cloke, 2014).

Thirdly, one quickly gained the impression of a homeless community forever in motion (Kawash, 1998; Jocoy et al, 2010). Most of the homeless individuals encountered were found to spend their days circulating through a complex – but ultimately limited – spatial geography. On the one hand, this mobility was key to the fulfilment of basic human needs – such as food, shelter and healthcare (DeVerteuil, 2003). On the other, it could frequently be characterised as coerced behaviour – with mobility an indicator of both power and

Fourthly, though sometimes conceived as passive recipients of policy, there were countless instances of individuals cleverly “deploying their creativity, competence and cultural knowledge to survive” (Duneier, 1999, p. 312). Doorways provided shelter; pipes and ducts offered warmth; and walls, ledges and steps served as resting and meeting places. As many writers have shown, “the urban environment both shapes and is shaped by all those who inhabit it” (Cloke et al, 2008, p. 241).

Finally, while bringing into stark reality the plight of the homeless experience, the maps also made references to the value of support that the participants had received and how their lives had begun to change since their engagement with services. In most cases, accommodation was identified as the most critical factor in ‘move on’. However, tenancies were frequently temporary and insecure. Though no longer ‘roofless’, individuals invariably remained ‘placeless’ (May, 2000); with ‘’the experience of being ‘housed’ and homeless…[being] blurred” (May, 2003, p. 40).

For us, the maps confirmed that the ‘emotional’ matters (Davidson and Milligan, 2004). Emotions, such as “pain, bereavement, elation, anger [and] love” (p. 7) are filters through which we come to know and experience the world, shaping both what we know and how we know it. They influence what we choose to research, as well as our methodological, analytical and interpretive choices thereafter. And they do so in a complexity of pre-cognitive and pre-conscious ways. One way of reconciling the ‘emotional’ and ‘subjective’ with the ‘logical’ and ‘objective’ is to adopt a posture of reflexivity. This entails critical reflection on the ways we affect and are affected by the research process. However, too often, we suggest, the importance of such reflection is downplayed, with reflexivity considered synonymous with self-conscious reflection, rather than with that which is instinctual – the consequence of a reflex (Matless, 2009).

This in turn suggested that those staple methods of social science – the semi-structured interview, the focus group and the questionnaire – fail to engage with those many aspects of everyday life lying outside of the “narrowly discursive” (Hitchings, 2010, p. 61). There are on occasions, thoughts, feelings and experiences that are simply ‘unspeakable’. In this context, the value of the homelessness map lies less in its capacity to engage an audience through its channelling of oral testimony, but in its capacity to engage an audience instinctively, emotionally and viscerally.

Our final reflection is that while particular aspects of everyday life elude straightforward attempts at representation, creative approaches to writing, mapping and image-making are just some of the ways by which local area researchers may seek to access this unconscious knowledge.

Adele Irving is a Research Fellow in the Department of Social Sciences and Languages, Northumbria University

Oliver Moss is a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Social Sciences and Languages, Northumbria University